![CHAPTER I DE TORIANO AND EARLIEST TORIAN FAMILIES Early church records in Soglio, Switzerland show the name as Traila de Torriano, then Torriano de Traila, and later Traila is dropped. Traila was similar to a clan and Torriano means of the tower showing they guarded the tower or lived near the tower. The late Peggy Chapman, using microfilmed church records in Latin, discovered in 1998 the earlier generations of this family. This first chapter is from her work, not mine. The family line as shown in the church records with the first known person is as follows. 1 Gaudenzio1 Traila de Turriani, born 1626, and later known as Lieutenant Gaudenzio Traila Torriani, died 5 September 1710, age 84. The name Gaudenzio may have come from St. Gaudenzio, the martyr who brought the Christian belief into the valley. The following people are found on the Family History Library, microfilm no. 1192790, item 2, church records from Soglio, Graubünden, Switzerland, of the Family History Library. Known children of Gaudentuis1 and [–?–] Traila de Turriani: 2 i. Pedri (Peter)2 Traila de Turriani, born and baptized 1656 in the Evangelical & Reformed Church of Soglio, Graue,

Switzerland as the son of Gaudenzio Traila de Turziani. Peter, son of the Lieutenant Gaudentuis of the Turriani, died 5 February 1733 at age 77. He married Maria Salis, 25 April 1688,[1] the daughter of Lt. Schertoruis Salis. Known children of Peter2 and Maria (Salis) Traila de Turriani:

4 i. Barbara3 de Turriani, born unknown, and died 5 September 1710 in Soglio. 5 ii. Anna3 de Turriani, born 1689 and died 19 September 1691 in Soglio. 6 iii. Gaud3 de Turriani, born and baptized 1691 and Gaudenzio, son of Peter Traila of the Turiani,

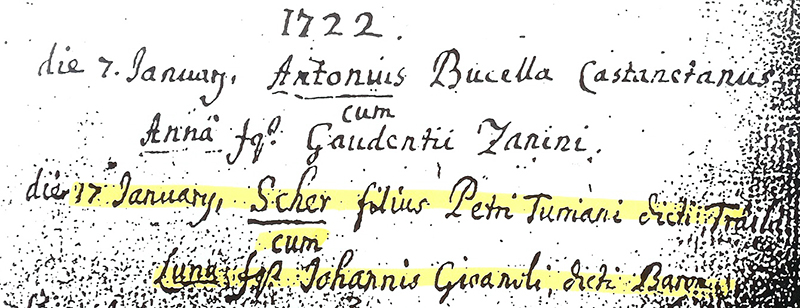

died 19 March 1695, age 2 years 4 months[3] in Soglio. 7 iv. Schertorio3 de Turriani, [later called Torian] born 1695 in Soglio, Switzerland; baptized 22 April 1695; and died about May 1748 in Lunenburg County, Virginia. Schertorius, son of Petri Turrianus also called Traila married (1) Luna Giovanoli on 17 January 1722 in Soglio and probably (2) Anne [–?–]. See the end of this chapter for an in depth discussion of his family. 8 v. John3 de Turriani, baptized 1699 and Gian (John) son of Peter Traila of the Turriani, died 15 June 1699 in Soglio. 9 vi. Anna3 de Turriani, baptized 1700 as Anna daughter of Peter Traila of the Turriani. She died 23 January 1715 and was buried on the 23rd. She was in the vineyard in the locality of Lolano? and fell headlong from very high cliffs and died at once, at age 15. 3 ii. Barbara Traila de Turriani, daughter of Lt Gaudentius Traila de Turriani, married 28 September [year unknown], Antony son of Sylvester Giovanila. The “de” part of his name may mean they descended from nobility. The Canton Graubünden in Switzerland is very close to the Italian border where the family originally came from. According to Peggy Chapman, the official language of the area was not German nor Italian but Romansh, which is used in the Swiss canton of Graubünden, however the church records were in Latin. The records of Schertorio in the United States show his name as Scher Torian rather than his baptismal name. In June 2008 Charles Sherrer, a descendant found in Chapter VII, vacationed in Switzerland and visited Soglio, Switzerland where our Torian ancestors came from. Soglio is a tiny, mountain town with a population of around 200. He took the following photos which give a glimpse of modern day Soglio. Peggy Chapman spent years researching for information about the ship on which the Torian family came to Virginia, the shipwreck off Lynn haven Bay, and stories about William Byrd settling Swiss Protestants in Virginia. She wrote to Lloyd’s of London; the NationalMaritimeMuseum, London, England; MarinersMuseum, Newport News, Virginia; the Public Record Office, London, England; and the Virginia State Library, Richmond, Virginia, and she hired a British researcher and found a number of articles that gave clues. The list of periodicals which led to her conclusions is included in the endnotes.[4]](images/u6500-97.png)

Soglio, Switzerland

Soglio with the church

Soglio

Mountains & churchyard in Soglio

Monuments in churchyard with familiar names of Giovanoli and Salis

Peggy Chapman reviewed the microfilm for the church in Soglio and said that Scher’s family disappeared from the church records about February 1738. This matches with the sailing of the ship Oliver from Plymouth, England in September 1738 with 300 protestant Switzers who sailed up the RhineRiver to Rotterdam and then sailed to England. The following lengthy story is from the website of John Blankenbaker and explains the voyage of the Oliver and is based on the work of Klaus Wust.

Voyage of the Ship Oliver

Nr 1476:

The voyage of the Oliver has its origins in a group of Swiss who had been recruited by William Byrd to occupy a tract of land that he wanted to obtain. The organization in Switzerland which had done the recruiting chartered the Oliver. The Swiss left CantonBasel in March of 1738 for Rotterdam. At about the same time, a group of 53 men, women, and children left Freudenberg from the Siegen area. In Rotterdam, the two groups were joined, and their fate became the same as the fate of the Oliver. Both the Swiss and the Freudenberg people wanted to go to Virginia. To fill up the Oliver, some Palatine redemptioners who wanted to go to Pennsylvania were added to it.

On June 22, five ships operated by the Hope firm, left Rotterdam for ports in England. The captains of the Winter Galley and the Queen Elizabeth headed for Deal. The Thistle, the Glasglow, and the Oliver headed for Cowes (on the Isle of Wight). It took some of these ships three to five weeks to get to the English ports. The captain of the Oliver felt that his ship was overloaded and he returned to Holland, where he resigned. The owners installed a new captain and sent the ship out again in early July. This time the Oliver made it quickly to Cowes, where it spent six weeks in preparing for the crossing. After setting out from Cowes, the Thistle and the Oliver found heavy seas that forced them into the harbor at Plymouth.

The Oliver did not leave Plymouth until the start of September. A ship that met the Oliver on the high seas brought in the report that the ship had lost its Captain, Mate, and 50 or 60 passengers, many of whom were children. They were also said to be short of provisions. By the start of winter, no news had been received in America of the ship and it was feared the Oliver had been lost.[5]

Nr. 1477

Reports from two passengers on the Oliver have been preserved, but it would be hard to tell that they pertained to the same ship. One telling of the trip says that the first six weeks were satisfactory, but that during the next ten weeks they were tormented by storms and contrary winds. They lost the mast of the ship and the Captain died. Because of the length of time that they were at sea, the food and water had been totally exhausted.

Early in January, the Oliver appeared off the coast of Virginia. It had been more than six months since the passengers had boarded in Rotterdam. At this point they had been without food and water for several days. When the ship was within two hours of Hampton at the mouth of the James River, the passengers grew impatient. They insisted, with a reinforcement by arms, that the Captain anchor and obtain some provisions. A party went ashore and the majority of the crew and passengers remained on the ship.

While the party was ashore, violent winds arose and the ship dragged its anchor until the ship's bottom scraped on the sea floor. Leaks followed and the ship filled with water. Forty to fifty persons were trapped and drowned between the decks. Two ships that lay near the Oliver provided assistance and put many people ashore. The weather was so cold that some people froze to death. An article in the Virginia Gazette newspaper mentioned that there were ninety survivors.

The group that went ashore to find provisions landed on an uninhabited island and they found nothing that would be of any help. When the winds came up, they were trapped on the land and could not take their boat out to the floundering ship. To survive the cold, they built a large bonfire. About two out of three of the passengers that boarded the Oliver in Rotterdam did not survive the trip.

The tradition that Meredith Funderburk relates, says that the source of his family was Hans Devauld Vonderburg, who was 14 years old when he sailed. Coming with him was his father and perhaps six brothers and two sisters. Devauld is the only one of the family who survived. It is remembered that three ships left together. Devauld's ship was wrecked off the coast of America, where he was picked up by another ship carrying Germans. He became an indentured servant. Later he met uncles and cousins here who had arrived in Pennsylvania on the ship Thistle in 1738.

The surprising thing about this story is the oral tradition was correct about many of its elements. There is so much that jibes with known historical facts that it must be concluded that the tradition did arise validly and has been preserved essentially correctly. So many traditions get embellished with the passage of time that the source events, if they were true to start with, are lost.

Meredith admits that his faith in the tradition had been weakened, but discovering the story of the Oliver has restored his beliefs.

Nr. 1478:

I have mentioned William Byrd (II) in connection with the ship Oliver. His involvement came about in the following way.

He obtained a patent in 1735 for 100,000 acres on the Dan River in Virginia, on the condition that he settle at least one family for every 1,000 acres within two years. Securing 100 families was not easy, but Byrd felt that his contacts with John Ochs, a Swiss promoter, would be fruitful. The first attempt to induce settlers to come to Virginia in 1736 was unsuccessful. Then Byrd turned to the “Heivetische Societät” in Berne. To promote the project in Switzerland, they published a booklet in 1737 entitled “Neu-gefundenes Eden” (New Found Eden), which described the land in Virginia. Like much promotional material, the booklet did not adhere strictly to the truth.

The Virginia agent of the Helvetian Society, Dr. Samuel Tschiffeli, had agreed to buy a large part of the Byrd property in his own name. Byrd used this to show the Virginia authorities that his partners were serious, and, thereby, he obtained an extension of time. Recruiting by the Helvetian Society was successful and the Society chartered a ship, the Oliver, to bring the colonists to Virginia. It was the only ship in the 1738 shipping season which was bringing emigrants from Europe to Virginia. The contingent from Freudenberg was taken on, in addition to the Switzers, even though Captain Walker felt that the ship could not carry that many passengers. Of the three hundred people who started the trip, fewer than one hundred survived the voyage. The worst part of the voyage, though it was only a small part of the whole ill-fated attempt, was the grounding and the sinking of the ship off the mouth of the James River in Virginia, after four months on the high seas. Both the Swiss and the Freudenberg emigrants were caught in the disaster. Of the eighteen family units from Freudenberg, only six are known to have any survivors.

Apparently, in addition to the Switzers and the Freudenberg people, some other Palatines were taken on board, even though these added passengers wanted to go to Pennsylvania. This was the case with the Vonderberg family, who had only one survivor.

There is a recorded story of one survivor who had an experience, much the same as Hans Devauld Vonderberg’s story, which was preserved through oral tradition. The sole survivor in the diary account of his own family was Samuel Suther. The Suther family of twelve people left their home on March 28, 1738. The only survivor was the boy Samuel. The father and two daughters died on the shores of England, spared the misery which was to come.

Crossing the Atlantic Ocean, they encountered thirteen storms, taking from the beginning of September to the beginning of January to reach the shore of Virginia.

Nr. 1479:

The owners of the ship Oliver requested one of the passengers to give testimony concerning whether there had been any failure by the owners or the crew in the care of the passengers on the Oliver. The man who did testify, Carlo Toriana, must have been paid well. He described the Oliver as a good and spacious ship (actually it was a coaster freighter, not a transatlantic ship). He notes that they left Holland early in July, without mentioning that the ship had left earlier but the captain turned around and went back, because he thought the ship was overloaded.

He says that after leaving Plymouth they sailed happily for six weeks (the passengers had been on board for more than two months when they left Plymouth and I doubt they were happy). Carlo goes on to say that after four months from Plymouth they sighted Virginia. He claims the wind had died at the arrival so the captain had taken the opportunity to seek supplies, even though there was food still left for everyone. With a little wind they advanced to within two leagues of the coast.

After the anchor was set, several Palatines mutinied against the captain and he was forced to use the longboat again taking him, 2 sailors, and 26 passengers ashore. A storm arose while the party was ashore and the captain tried to go back to the ship but couldn't. It was so cold that some of the shore party, wet from the attempt to reach the ship, died. A fire was lit and the party spent the night in the woods. In the morning they found that the ship had sunk with the stern sticking out of the water. A few people were clinging to it. Some of these people were saved by another ship.

Carlo said that not more than sixty people of those who had embarked remained alive. Over the next two weeks much effort was spent on recovering personal effects and rigging from the ship.

All of the passengers were well fed and well treated and provisions were never lacking was the claim of Carlo. He completely absolved the owners of the ship of negligence or of being responsible for what happened in any way.

Klaus Wust, in preparing his material for the article in Beyond Germanna used his research, which he had reported in the Newsletter of the Swiss American Historical Society, Vol. XX, No. 2. The Toriano statement was found by Klaus as a French document in Rotterdam, in the Notorial Acts, August 4, 1739. The statement of Samuel Suther was from the Reformed Church Messenger of May 10, 1843, as a part of the obituary notice for David Suther, son of Samuel, and was based on an account in a diary.

Based on this account it is believed that Scher’s wife Luna and some children died on the journey or during the shipwreck. Those surviving were Scher Torian and his son Peter (Chapter II), and daughter Mary (Chapter XIX). Sons Andrew (Chapter X) and Scare (Chapter XX) were also probably on the ship.

Bess Torian Palenske's story of the family

While researching the Torian family, Peggy Chapman discovered a document that was filed with the Kentucky Historical Society. It was a Torian genealogy written by Bess Torian Palenske, a descendant of Nathaniel Torian (Chapter XVIII). It is a fascinating story that she pieced together (most of it accurate) from her research in the 1930s, 1940s, etc. It is amazing that she was able to gather so much information without the aid of modern day computers, copy machines, Internet and microfilm. She did it the old fashioned, reliable way and visited courthouses and wrote lots of letters. More information about Bess is found in Chapter XVIII. The following foreword to her genealogy was shared with me in 1997 by the late Mack Dickey and is an excerpt from the material Bess wrote.

The records used in the genealogical research of any early American family are usually found in old Court House records—that is proceedings, wills, deeds, marriages, and other filed papers. Because the county formation and the location of court houses affects the recording of data, it becomes often necessary to follow lineage of the county in which the first records appear.

The Torian family in America first settled in the Southern Virginia area in a section now known as Halifax County. We know the location of the plantation and the approximate time of settlement which was several years before Halifax became a county. It was necessary for those people to journey to a distant court house to do their business. For that reason we should know the lineage of Halifax County and the surrounding counties—that is if we wish to learn something about the family of an earlier date than is found at Halifax County. To do this we begin in the first coastal settlements of Southern Virginia and follow the counties west as they were formed.

The general movement of the incoming population was up the rivers. Then, as both Church and State were under English control, new parishes were formed and named along with each new county. The first settlements followed both sides of the James River up to the mouth of the Appomattox River, at first forming the counties of CharlesCity and Henrico. The large Parish of Bristol covered the whole valley of the Appomattox. This river was the first great highway to the Southern tier of counties. Then as population spread, CharlesCity County was cut into normal size and Prince George County was the name given to the whole valley of the Appomattox with the village of Prince George Court House as the county seat.

In 1732 Prince George County was cut away and all the land westward and north to the top of the Blue Ridge Mountains and south to the North Carolina line became Brunswick County, St. Andrew’s Parish. Lawrenceville Court House became the county seat. In 1746 Brunswick County was cut away and the section west was called Lunenburg County, Cumberland Parish, which again also embraced all the section west and south, with Lunenburg Court House becoming the county seat. Still later in 1752 Lunenburg was cut off and the section west was called Halifax County, Antrim Parish. Again in 1756 the southern part of Lunenburg was made into Mecklenburg County, St. James Parish. Still later part of Halifax County was made into Pittsylvania County, Camden Parish, on to the west.

Now, having followed the lines of county formation to Halifax we turn about and go into the county just preceding Halifax, which is Lunenburg. In the year 1746 at September Court appeared 3 emigrants, Scher Torian, Peter Torian, and Silvester Gianane, “Severally took the oath of His Majesty’s Person and Government and subscribed the test in order to their naturalization.” This fact was duly recorded on the county books and after many, many years—forgotten. (Order Book 1, page 64, Halifax Court House.) It was not until about 1912, after the passage of more than one hundred sixty years, that this record of naturalization was found by one who came searching for Torian family history. At this time and for many years, there was speculation as to whether Scher and Peter were father and son or two brothers. And since no other legal papers were then found there was no positive proof in either history.

However in 1748, a will had been written by one Scher Torian and left in Lunenburg Court House where it was not duly recorded but was misplaced. It was forgotten until in 1938, it was found by Mrs. Rosa Neblett, a genealogist working at Lunenburg Court House. In 1938 I went to Lunenburg, previous to the finding of the will, to search for family history. I found only the old naturalization paper of 1746 which the clerk copied and certified for me, a few deeds and marriages, but little else. However, I did meet and talk with Mrs. Neblett. She was a refined and lovely lady and quite old. She was very friendly and helped me a great deal. After return home she continued to “browse” around and quite by accident found the Scher Torian will in an old cabinet. While I did not find this will myself, I feel that I was indirectly responsible for Mrs. Neblett doing so.

In this will Scher names a wife, a daughter Mary, and three sons Scher, Peter and Andrew. Later, three men of these same names in their own wills, recorded in Halifax County, speak of each other as brother and of a sister Mary, whose will is also available. In this way we have accounted for two Schers, a father and a son. And as no other wills or legal papers have been found to contradict the theory, I assume that the two men who were naturalized at Lunenburg in 1746 were brothers.[note, now we believe they were father Scher and son Peter] A further search at Lawrenceville Court House which preceded the forming of Lunenburg County has revealed no further information. Probably the reason for the will’s not having been recorded was that Scher states in it his desire that the court have nothing to do with it except record it. Apparently nothing at all was done and it lay around until it became lost in the vast amount of papers which usually accumulate around a county court house.

Of course this elder Scher’s will led to more speculations. Why were not the elder Scher, his wife, son Andrew, and daughter Mary not naturalized? If they were, the papers are recorded at Lunenburg or in some other court house and have never come to light. Perhaps they were never naturalized.

It may have been that the original Brunswick County was a little lax in these matters for a period because of the anxious desire to colonize the vast stretches of wilderness. In 1737, Brunswick County, together with the English Crown and William Byrd, who also owned a large tract of land on the Southern border of Virginia, began a campaign offering many inducements to Protestants who would settle along the Roanoke and Dan Rivers.

After 1746 we find few Torian records at Lunenburg and so far none at Brunswick where we hope to search further, so we turn again to Halifax County where we find many records after 1752. However, after the turn of the century many of the descendants of the original Scher Torian began to feel the call of the West and South; into Mississippi, Tennessee, Georgia, Louisiana, with the largest colony settling in Kentucky. After all the YadkinRiver and Boone’s influence were not so far away!

“Yes,” they used to say in Kentucky, “My grandfather and his family lived under a wagon bed while they made the first crop and when he died he was worth a hundred thousand dollars.” Not so bad for those days! However this may have been as I do know that many of the Kentucky descendants of Peter were prominent businessmen in Memphis and New Orleans in decades long gone by. Those of Andrew’s descendants who stayed in Virginia and North Carolina had hundreds of acres in tobacco but the Civil War brought ruin and heartbreak just as it did to many a flowering plantation in the South. My grandfather, Robert [Robert Andrew Torian] took a broken heart with broken dreams and went west too late in life to retrieve all that his youth had brought him.

Where did the family come from?

I shall not attempt in this foreword to follow all these families because I wish to come to a question infinitely more important to the whole group. From what country did Scher and his family come? Now appearing with Scher and Peter, probably the original Scher’s sons, at the Lunenburg Court House was Silvester (Silvanus) Gianane, an Italian. Silvester was probably a friend and neighbor or even perhaps a relative because his name appears as one of the administrators of Scher’s will and it also appears on other papers concerning the family.

The Italian name seems to have been difficult for the English scribes to interpret because it appears spelled in various ways. In the will it is spelled Caluanol, yet it appears Gianane on the naturalization paper. On other legal papers it appears as Juriour, Jionour, Jounol, Junall, and finally Junel and Junell. We must conclude that each person writing it tried to list it as it sounded. Silvester himself must have finally accepted Junel as the English spelling because it so appears on his own will written in 1773 in Halifax County and witnessed by Andrew and Peter. Silvester being a close friend and naturalized with Peter was as Italian. The name Torian coming also from an Italian name Torianna, the inference is clear, Scher was an Italian.

This is also borne out by traditions in the family that they came from the old Italian family of Torriano. This legend was found in the Louisiana branch of the Andrew Torian line. Undoubtedly it was known and forgotten long before in Virginia. The trials and isolation of pioneer life would make a family forget its history as the years went by. Virginia Torian, the granddaughter of Thomas [Sr. added by author], son of Andrew, lived as a child in Virginia. Later she moved with her parents to Bayou Tech, St. Mary’s Parish, Louisiana. She married into the wealthy Walters family of Baltimore. Perhaps it was then she found time and means to do family research. She may have been inspired by stories of her childhood, or even by a desire to prove her standing equal if not above her husband’s family! However, this, she is said to have done much research in this matter. It is regrettable that her material was lost and that she had no issue to carry on. The story comes down to us in old letters or by word of mouth. Her brother Walter in later years carried the story back to Virginia when he went East to school and spent his weekends at the plantation of his grandfather Thomas Torian near Halifax.

There is also today in the possession of a descendant of Thomas living near Halifax a copy of an old Stradivarius violin, dated 1742 which he inherited from his grandfather Elijah, son of Thomas. I have seen it and held it in my hands. If only the old, old wood and the quaint decorations on it could speak! Of course this violin proves nothing; yet it suggests a world of possibilities, could one build its story. Dancing in Italian streets, echoing through the Swiss Alps, moaning on stormy seas, and signing with contentment and peace at the last!

As to the pronunciation of the name Torian. Today in America it seems always to be pronounced as in “historian”. However, the early Virginia and North Carolina pronounced it “To-ran” accenting the last syllable,” The children of North Carolina slaves which my grandfather brought with him west of the Blue Ridge, called my mother, Mis “To-Ran”. She didn’t like it so she asked them to call her Mrs. Torian. And so our family being removed from the North Carolina and Virginia influence soon came to pronounce it as in “historian.”

By correspondence with officials of the Archives of Berne, Switzerland, Sidney Wilson of California, who has done a great deal of research on the family, learned that a man named Pieter (Peter) Torian appeared in Berne from the Chiavenna Valley about 1600. He was a dyer and nothing more was heard of him. Also he learned from a list of Swiss emigrants, that in 1734 a man named Alexander or Abraham Torian had asked for a permit to sail to the Carolinas. Because of the inclement weather on the high seas he was not permitted to sail and nothing more was heard of him (Faust and Brumbaugh, List of Emigrants to the American Colonies), So we find Torians in Switzerland thinking about and hoping to come to America in 1734; we find Torians being naturalized here in 1746, so we naturally infer that our family of Torians came from Switzerland.

About 1907 in Paducah, Kentucky, I met Owen Torian. He was the youngest child of Jacob, son of Peter. Born in Virginia about 1827, he moved to Kentucky as a small child with his parents. Being 90 when I knew him many things were confused in his memory of his people in Virginia. He thought they had come from Scotland and that his great grandmother had died and been buried at sea. Scher was his great grandfather and we know that Scher had a wife in 1748; though it is possible that he could have lost a wife at sea……

Bess Torian Palenske

A little history of the area

Lunenburg County was formed by the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1745 and later in 1752 Halifax County was formed from a portion of Lunenburg County.

All the land lying on the southside of Black Water creek, and Staunton River to the confluence with the river Dan and from thence to Aaron’s creek to the county line, shall be one distinct county and parish and called and known by the name of Halifax and Parish of Antrim.[6] Early court order books often show who was appointed to assist in clearing new roads at specific locations. Some wives who relinquished their dower rights to land sold by their husbands are named in the court orders but not in the recorded deeds in the deed books.

So great was the influx of new settlers into Lunenburg County that seven years after its establishment it was deemed necessary to divide this great domain and create a new county. Accordingly in February, 1752 the General Assembly of Virginia enacted. That all that part thereof lying on the south side of Blackwater Creek and Staunton River, from the said Blackwater Creek to the confluence of the said river with the river Dan, and from thence to Aaron’s Creek to the County line, shall be one distinct County and parish, and called and known by the name of Halifax and parish of Antrim; and all that other part thereof on the north side of Staunton River, from the lower part to the extent of the county upwards, shall be one other distinct county, and retain the name of Lunenburg and parish of Cumberland.[7]

In the early records the Torian name was indexed under the letter “D” and entered as Scher Torio Detorianio. The anglicized name Scher Torian was often recorded as Scare Torian in Halifax County records. The name Silvester Gianano became Silvester Jouniours in Lunenburg records and Sylvester Juniel in Halifax records.

Now that we have some background on the family, let’s turn our attention to Scher Torian who is the oldest immigrant of this family in the United States.

Scher Torian

7. Scher3 Torian, (Pedri Traila de Turriani2 , Gauddenzio Traila de Turriani1)

Scher was baptized in Soglio, Graubünden (Canton), Switzerland on 22 April 1695 as son of Pedri Traila de Turriani.[8] He was listed as the son of Pedri (Peter) Traila de Turriani who married Mary Salis on 25 April 1688. According to Peggy Chapman, the first church records of Soglio are dated 1650 and the family was there as of that date, however they originated in Italy. Scher was also known as Schertorio and the family surname was shown as Turriani de Traila, Traila de Turrani, Turriani, and later Torian after he moved to Virginia.

Scher’s marriage record shows 17 January 1722, Schetorius son of Peter Turriani also called Traila, married Luna daughter of Johannis [John] Gianoli (Giovanila, Gioanili) dicti Baron [called Baron][9] and Luna Ruinell, born 1676. Luna was the daughter of Andrea Ruinell and Rosa Heinz di Aver.

Scher Turriani and Luna Gioanoli’s marriage, 1722

![Known children of Scher3 and Luna (Gianol) Torian: 10 i. Petrus4 de Turnaris [Peter Torian] was baptized 19 August 1722 in the church in Soglio.[10] His death record

in the church shows Peter, son of Schertorius Turriani died 27 February 1724, at age 1 and ½ years. 11 ii. Anna4 Turriani was baptized 9 January 1726 in Soglio. 12 iii. Petrus (Peter)4 Turriani [later Torian] was born 10 September 1727 and baptized 17 September 1727 as

Petrus, son of Scher Turriani in Soglio.[12] He died about 25 May 1812 in Halifax County, Virginia. See Chapter II. 13 iv. Andrew4 Torian, born between 1727 and 1738 and died in December 1793 in Halifax County, Virginia. See Chapter X. 14 v. Maria (Mary)4 Turriani, baptized 3 August 1729 in Soglio, and died just before 15 August 1781 in

Halifax County, Virginia. See Chapter XIX. 15 vi. Luna4 Turriani, baptized 13 August 1732 in Soglio and recorded as daughter of Scher. 16 vii. Johannes4 (John) Turnari de Turianio, 23 March 1735 in Soglio. 17 viii. Scare4Torian, born between September 1728-1736 and died in November 1780. See Chapter XX. It is unclear whether Scher Torian’s last two children are the children of his first wife Luna or his second wife Anne. No baptismal record exists for them in the church at Soglio which supports the theory that they were born elsewhere. No naturalization record exits for them in Virginia in 1746 which could indicate they were younger than age 21 in 1746 and didn’t need to be naturalized or that they were born in Virginia and didn’t need to be naturalized. Bob Skinner a descendant in Chapter IV theorized that Andrew Torian was born before 2 July 1729. He based this on the fact that Silvester Juniour deeded 200 acres to Andrew on 2 July 1750 which was the land Andrew’s father Scher had left him when he died. Bob thought this might have been when Andrew turned 21 although there’s no way to know for sure. Bob also theorized that Scare Torian was born before 20 October 1736. He based this on the fact that on 20 October 1757 Peter Torian deeded 127 acres to Scare Toryan that formerly belonged to his father Scher and this might have been when Scare turned 21. The result is that we can’t prove when they were born based on available known information or be sure whether Luna or Anne was their mother. The following is a chronology of what is known about Scher Torian. 1739 Probably arrived in January 1739 in Virginia aboard the ship Oliver. 1740

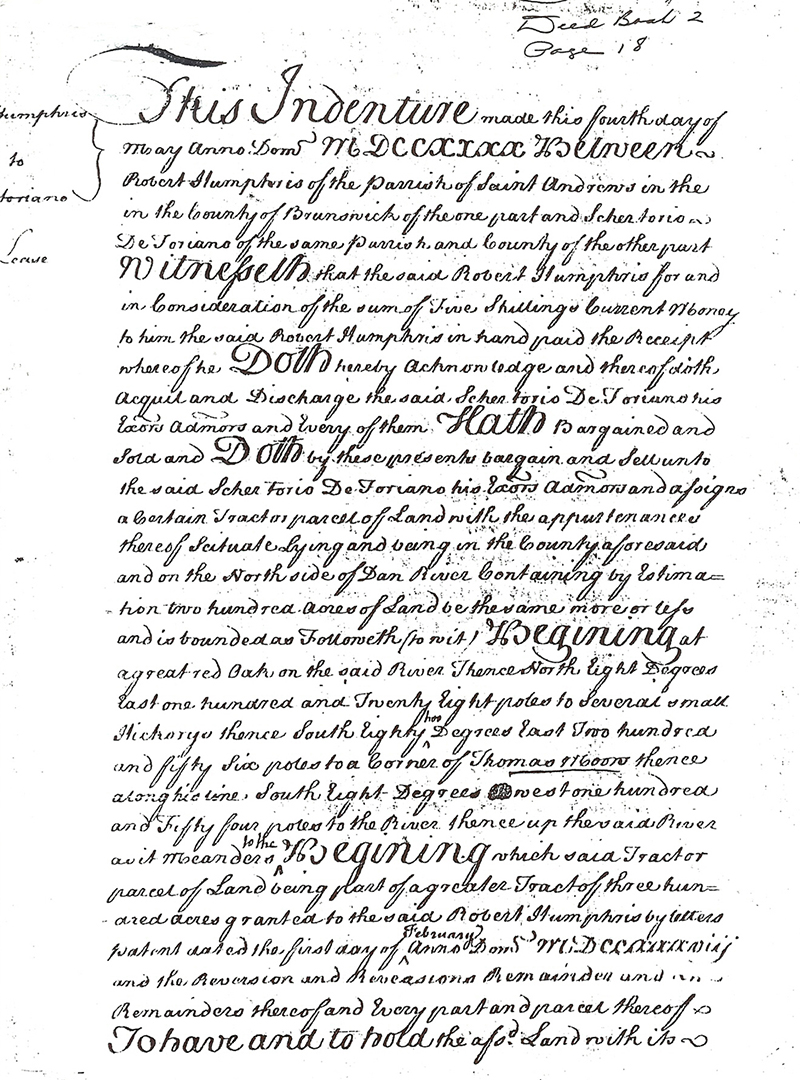

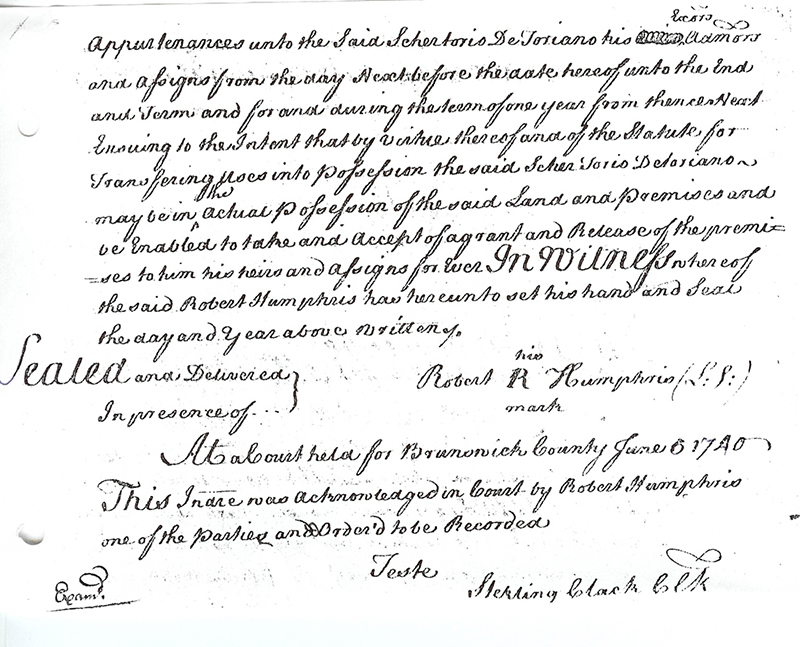

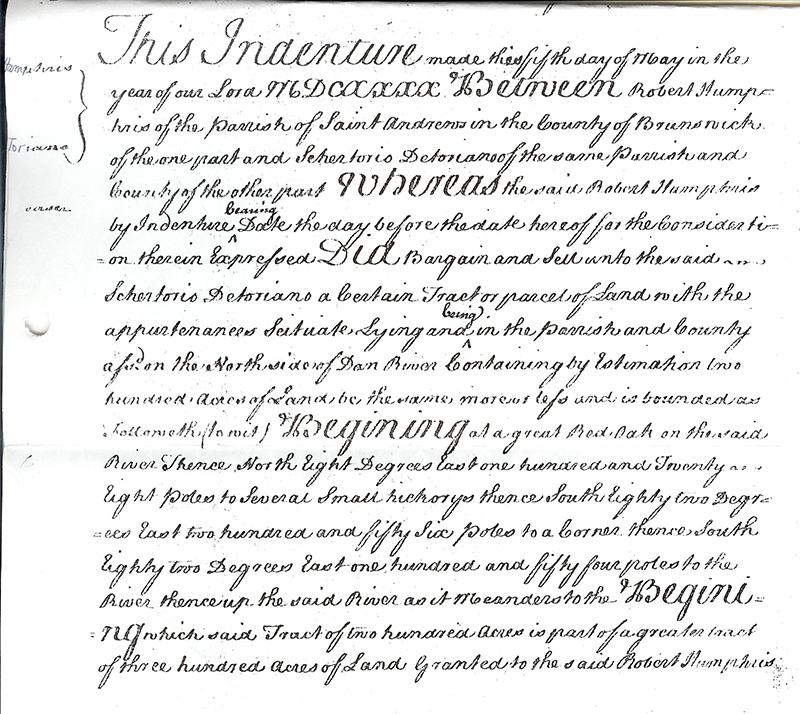

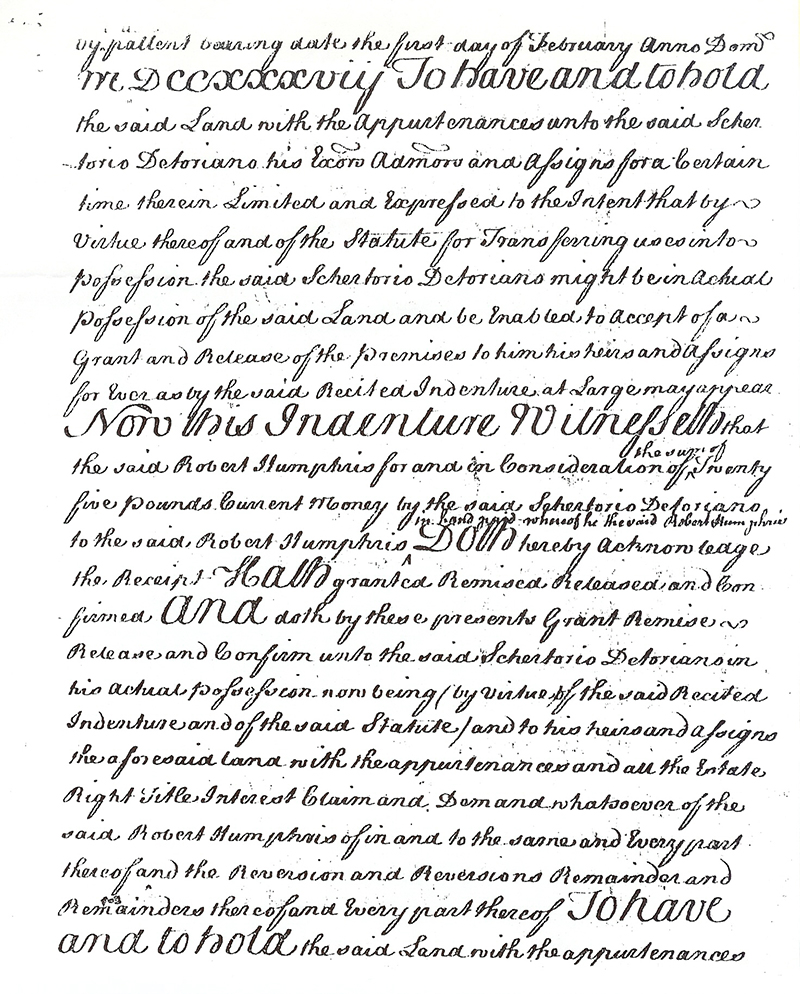

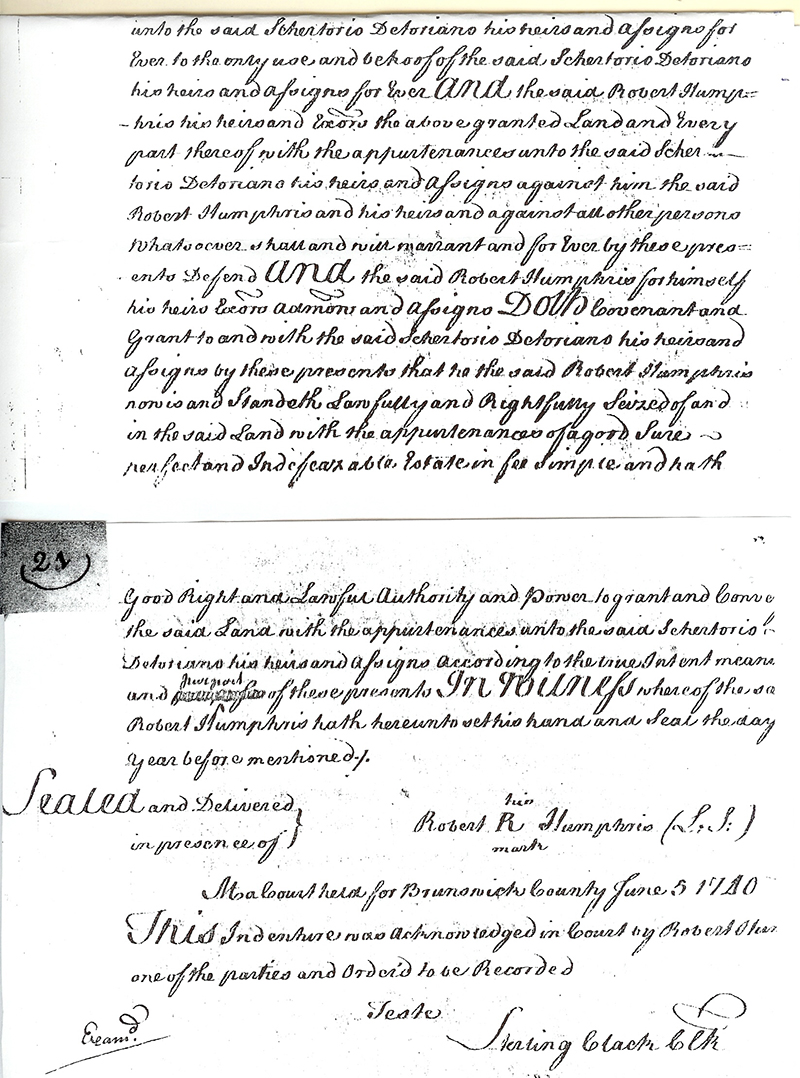

4 May, a lease and release from Robert Humphris of St. Andrews in Brunswick County to Schertorio De Toriano, of the same county and parish, for 25 pounds, a tract of land of 200 acres on the north side of the Dan River part of a larger tract of land granted to Robert Humphries by patent 1 February 1738 bounded by land of Thomas Moon. Recorded 5 June 1740.[13] The seller conveyed a lease to the land, then the seller executed a release to grant to the buyer a reversion of the seller’s interest. This transferred title to the buyer since he owned the current and future interests in the land. See copies that follow. 1746

At a Court held for Lunenburg County, Virginia on the first day of September in the Sixth Year of the Reign of our Sovereign Lord King George the Second and in the year of our Lord God MDCCXLVI Scher Torian, Peter Torian and Silvester Gianano came into Court and severally took the usual Oaths to his Majestys Person and Government and Subscribed the Test in Order to their naturalization.

[14] 1748

Scher Torian signed his will. 1759

August Court, Halifax County, Virginia. On the petition of Andrew McCool, it is ordered that Robert Wade Jr., Abraham Maury, and William Stokes, Gentlemen, do state and settle and account of the said Andrew McCool’s disbursements for the orphans of Schear [sic] Torian, dec’d (with whose widow the said Andrew intermarried), and they also law out & ascertain her dower.

[15] Scher Torian prepared a will a few days before he died in May 1748. It was transcribed by Peggy Chapman as follows with original spelling, capitalization and punctuation. In the name of God, amen, I Scher Torian of Lunenburg County, in the Parish of Cumberland, being in Low state of health but perfect memory do make and ordain this my last will and testament.

First — I give and bequeath my soul to Almighty God in hope of the Glorious Resurrection. I believe in the true Messiah and that I shall be saved by his merits and after this natural life, desire to be buried by my Executors-after mentioned in a decent manner and my personal charges to be paid out of my Estate.

I ordain William Wynne and Silvester Galuanol entire executers of my goods and chattels to be distributed as follows:

Item: I give and bequeath to my loving son Peter Torian and Scher Torian, my son, the land where I now live to be equally divided between them by my Executors.

Item: I give and bequeath to my loving son, Andrew Torian, two hundred acres of land being the half of a trak of land purchased of Silvester Galuanol and his equal part of the movable Estate.

I give unto my loving daughter, Mary Torian her equal part of my moveable Estate.

Item: I give unto my loving wife her being upon the said land her equal part of my moveable Estate and I desire that the Court may have nothing to do with this will, only permit it to be recorded. Given under my hand and seal the 13th day of May in the year of our Lord 1748. SCHER TORIAN

Sealed and delivered in the presence of us being presented before.

James Wood

Peter Torian

Proved May 16, 1748 J.T. Waddill, Jr. Clerk, Lunenburg Co., Virginia certified that the foregoing is a true copy of the will of Scher Torian as certified by me in 1938 for Mrs. Rosa Neblett, a genealogist, who worked for many years as such in this office. I further certify that I saw and compared the said copy with the original will in 1938; that the original will was never recorded and that it has been misplaced or lost and cannot now be found. In testimony thereof, I have hereunto set my hand and affixed the seal of the Court this 24th day of October, 1957. Since Scher Torian died in May 1748, Anne apparently married Andrew McCool after May 1748 but no marriage record has been found. Anne W.[–?–] Torian McCool was found by Peggy Chapman in the Halifax County, Virginia tax lists in 1791 so she apparently died after that date. The following personal property records in Halifax County were found by Peggy Chapman.

[16] 1783-1784 Andrew McCool. 1785 Anna/Anne McCool was taxed as a neighbor to Peter and Andrew Torian. Anna McCool 1 male, 7 blacks age 16 ,

7 horses, 25 cattle. 1786 Taxed next to Andrew Torian. Anne McCool, no males, 1 black under age 16, 1 black age 16 , 3 horses, 15 cattle. 1787 Ann McCool no males, 2 blacks age 16_, 3 horses, 15 cattle. 1788 South District, Ann McCool, 2 blacks age 16 , 3 horses. 1789 South District. Ann W. McCool, 2 blacks age 16 , 3 horses. 1791 Ann McCool, 2 blacks, 3 horses. List is not clearly labeled for the year. Ann McCool was not mentioned in the Vestry Book of Antrim Parish, Halifax County, Virginia 1752-1817. Anne [–?–] Torian McCool’s husband Andrew signed his will 4 March 1785 in Halifax County. Half of his estate was divided amongst Andrew Torian’s children to wit: Thomas Torian, Scar [sic] Torian, Andrew McCool Torian, Nancy Torian, Sally Torian, & Polly Torian and their representatives to them and their heirs forever.](images/u6489-171.png)

Lease of Land, Schertorio De Toriano, May 4, 1740, p. 1

Lease of Land, Schertorio De Toriano, May 4, 1740, p. 2

Release of Land, Schertorio De Toriano, May 5, 1740, part 1

Release of Land, Schertorio De Toriano, May 5, 1740, part 2

Release of Land, Schertorio De Toriano, May 5, 1740, part 3

— NOTES —

The following abbreviations are used in these notes.

Family History Library – FHL

[1] FHL film 1192790, Registri ecclesiastici 1650-1875, Evangelisch-Reformierte Kirche Soglio (Graubünden) Records; baptisms, deaths, marriages 1650-1760, item 4 is 1760-1838 & 1837-1875, p. 15

[2] FHL film 1192790, Registri ecclesiastici 1650-1875, Evangelisch-Reformierte Kirche Soglio (Graubünden) Records; baptisms, deaths, marriages 1650-1760, item 4 is 1760-1838 & 1837-1875, p. 9.

[3] FHL film 1192790, Registri ecclesiastici 1650-1875, Evangelisch-Reformierte Kirche Soglio (Graubünden) Records; baptisms, deaths, marriages 1650-1760, item 4 is 1760-1838 & 1837-1875, p. 9.

[4] Virginia History Magazine, Vol 11: 371, 380-381, 386-387; Vol 12: 283; Vol 13: 281-283; Vol 14: 116-117, 120-121; Vol 35: 177-189, 263-265.

Virginia Calendar of State Papers 1652-1791, Vol I, edited by Palmer, p. 222.

William and Mary Quarterly, 2nd Series, Vol 1, p. 195-197; 2nd Series, Vol 6, no. 4, p. 306-307;, 3rd Series, Vol 9, no. 4, p. 539-542.

Pierre Marambaud, William Byrd of Westover 1674-1744, p. 53-55.

Virginia Gazette, no 121, November 17, 1738-November 24, 1738, p. 4, col. 1; no 128, Friday, January 5, 1738 to Friday, January 12, 1738.

Edward Wilson James, ed., Lower Norfolk County Virginia, Antiquary, part II, p. 37-39.

Virginia Cavalcade, Vol 36, no. 2, p 88-95.

[5] <http://homepages.rootsweb.com/~george/johnsgermnotes/germhs60.html>, The website is entitled Germanna History by John Blankenbaker, Germanna History Notes, page 60, used with permission.

[6] Marian Dodson Chiarito, Vestry Book of Antrim Parish, Halifax County, Virginia 1752-1817 {Nathalie, Virginia: The Clarkton Press, 1983).

[7] Maud Carter Clement, The History of Pittsylvania County, Virginia (J.P. Bell Company, Lynchburg, Virginia, 1929), p. 57

[8] FHL film 1192790, Registri ecclesiastici 1650-1875, Evangelisch-Reformierte Kirche Soglio (Graubünden) Records; baptisms, deaths, marriages 1650-1760, item 4 is 1760-1838 & 1837-1875, p. 151.

[9] FHL film 1192790, Registri ecclesiastici 1650-1875, Evangelisch-Reformierte Kirche Soglio (Graubünden) Records; baptisms, deaths, marriages 1650-1760, item 4 is 1760-1838 & 1837-1875, Item 2. Text in Latin.

[10] FHL film 1192790, Registri ecclesiastici 1650-1875, Evangelisch-Reformierte Kirche Soglio (Graubünden) Records; baptisms, deaths, marriages 1650-1760, item 4 is 1760-1838 & 1837-1875, p. 240.

[11] FHL film 1192790, Registri ecclesiastici 1650-1875, Evangelisch-Reformierte Kirche Soglio (Graubünden) Records; baptisms, deaths, marriages 1650-1760, item 4 is 1760-1838 & 1837-1875, p. 52.

[12] FHL film 1192790, Registri ecclesiastici 1650-1875, Evangelisch-Reformierte Kirche Soglio (Graubünden) Records; baptisms, deaths, marriages 1650-1760, item 4 is 1760-1838 & 1837-1875, p. 261.

[13] Brunswick County, Virginia Deed Book 2: 18.

[14] Lunenburg County Virginia Circuit Court, Order Book 1: 64, copy courtesy Peggy Chapman.

[15] Halifax County, Virginia Court Orders 1758-1759 (Miami Beach, Florida: TLC Genealogy, 1998), p. 107, August Court 1759, Plea Book 2: 464.

[16] Halifax County, Virginia Personal Property Tax Lists, 1782-1791 (Miami Beach, Florida: TLC Genealogy, 1998).

© Marian McCreary 2015